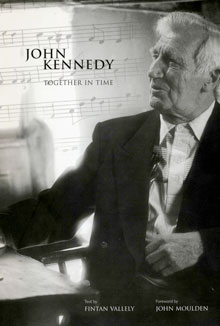

John Kennedy · Together in Time

Edited by Fintan Vallely. Text by Fintan Vallely. Foreword by John Moulden. Main photography by Gary Parrott; additional images Fintan Vallely. Published by Loughshore Traditions Group. (Co. Antrim, 2001). Music and index. 88pp, spiral bound.

Compact disc: John Kennedy: Together in Time. Loughshore Traditions Group. (Co Antrim, 2001). LS 001.

Summary

Flute player and singer John Kennedy was born at the hamlet of Craigs, just north of the village of Cullybackey in Co. Antrim. He began work at the age of fourteen in the linen trade, the staple industry of his area. So began an association with outstanding fiddler and singer Hughie Surgenor which saw them perform together for local socials and dances, step out playing fifes to Lambeg drumming, and sit in on sessions in the early years of Traditional music revival. John himself fifed on the Twelfth, instructed local marching bands, and in 1975 began teaching dance music at Dunloy and Portglenone CCÉ classes. This produced not only some outstanding flute players like Deirdre Havlin of Ballymoney, but inspired John to compete himself, gaining him many awards for song in the quarter century since. In the early years of his retirement in 1993 he began composing tunes and setting the words of local poets’ verse to music. Here is the life story of ‘the bard of Cullybackey’, his songs and his tunes, all brought to the eyes and ears of a wider public for the first time.

Published by Lough Shore Traditions Group, Co. Antrim

Extract from John Kennedy's words:

". . . There was two oul’ boys sat beside the fire an’ they w’r fiddlin. There was another boy sittin smokin the pipe, listenin to them for about half an hour, an’ they finished. An’ one of them said to the boy "What d’y think of that?"

He says "I wouldnae know".

"Well you know a brave lot when you know that you don’t know …”

Introduction

A word from Ulster’s man of songs

John Kennedy is, an ordinary man. A man who has worked with his hands for almost all of his 73 years, who lives and has always lived within a few miles of where he was born. John Kennedy is an extraordinary man too, a lifelong musician on whistle, fife, flute, banjo-mandolin and accordion. A teacher of music, a singer of old songs, a maker of songs; a lilter, a composer of tunes, a storyteller – and now a maker of flutes. His name is familiar to people who value the arts of the community, what used to be called the “folk-arts.”

John learned songs from his family and within the community. He learned tunes from his work-mates and from his mother who learned many of them from the Athlone broadcasts of Radio Éireann. The tunes he learned locally were mainly fifing tunes, he played them to accompany Lambeg drumming, in flute bands and later taught them to accordion bands when flutes went out of fashion. It may be a surprise to some, but the musical traditions of the area were not exclusive ones, so after the band practice the accordions turned to playing the jigs and reels current in the area and picked up from the radio. It was after this that John was asked to teach whistle and flute to the children of the Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann branches in Portglenone and Dunloy. His interest in songs revived and he took part in competitions, winning All-Ireland titles on several occasions.

He has enormous knowledge of the songs, the music, the singers and the players of his area. He knows how the tunes were used. He knows what they mean to the people. He has played in flute bands on the 12th July he has travelled to Wexford to sing songs from Ulster. He is uncompromisingly himself, a passionate musician first and foremost, and he has won the respect of all who know him, in all the aspects of his musical life.

This book and CD set is a tribute to John from some of his friends .He taught them music and he taught them honestly. He showed them himself and he allowed them to be themselves. They recognise the importance of his music, whether it serves to mark the time for Orange marches, to steady the rhythm of a Lambeg drum, or to give time to Irish dancers. They realise that he represents the musical life of the countryside at a time when there were not “two traditions” and they rejoice in the completeness of musical education he gave them. That he did so at a time when “the troubles” were making small differences large, is remarkable in itself. Some of his former pupils join him on the CD, playing the music both he and they love, and in which they find no differences.

John Kennedy may be a man of the people, but he is a man of all the people - honour him.

- John Moulden, July 2001

Epilogue

". . . I have great admiration for John, and I've always envied him for the way he could take both sides with him. He could sing and play for a weekend at a fleadh cheoil, and he could step out and play the fife on the Twelfth. He is a great inspiration to so many people . . . "

- Rosie Stewart, singer, Derrygonnelly, Co. Fermanagh

Review by Tom Munnelly

In his foreword John Moulden describes his subject as “uncompromisingly himself” and those of us fortunate enough to know this most musical Antrim man will be aware of just how accurate this description is. Fortunately there are also a number of other people in John’s locality who, unusually, recognized a prophet in their own land and sought to acknowledge his worth locally and proselytize his uniqueness more broadly. The Loughshore Traditions Group was formed in May 1998 “specifically to compile and record in book and audio form the music, song and life of John Kennedy.” Many of the members are fellow musicians and former pupils of Kennedy who are deeply convinced of the value of Kennedy’s contribution to the Ulster repertoire, not only because it transcends cultural barriers, but also because of his great individuality which has made its mark on Co. Antrim and south Derry in particular.

Having such a genesis, there is always the possibility that the end product would be an uncritical hagiography but the decision to recruit Fintan Vallely to work with the subject averted that danger. But before discussing the prose and musical content of the book it is worth calling attention to a physical description of the book itself. It is A4 in size and spring-bound. Such binding is never very aesthetic. However, the reason for using it, so that the book opens completely flat to facilitate maximum access to the many pages of music, is ultimately a good decision. The paper used is of such high quality as to be almost card. This allows for magnificent reproduction of the music and photographs. The photographs consist of older pictures of Kennedy through the decades playing accordion, whistle and fifing at the head of lambeg drummers in Orange parades. The newer photographs by Gary Parrot are nothing less than stunning. His portraits are redolent of Kennedy’s humour and intelligence and his pictures of the buildings and landscape among which Kennedy grew up are haunting. The sections of the book are divided by full-page pictures which are overlaid with opaque pages containing commendations and comments on Kennedy from many prominent musical colleagues. It really is most refreshing to see such marvelously high production values in a work on a traditional musician.

The book consists of the results of many hours of interviews with Kennedy, edited and transcribed by Fintan Vallely. The latter is a well known flute player himself as well as being one of the best known writers and commentators of traditional music in Ireland today. His evocative writing captures well Kennedy’s dialect (“more Scots than Irish”) though his reproduction of this in the text is never obstructive or confusing. His deep knowledge of flute and fife music results in several extended passages on the historical evolution of this music and this erudition adds immensely to the understanding of the context of Kennedy and his music. Among the factors which this reviewer found fascinating was Kennedy’s belief that his accuracy of rhythm is owed to working for years in the mills and absorbing the beat of the belts and pulleys among which he wrought. The story of John’s life is covered in great detail. Not only do we get the chronological facts as he journeyed through life, fascinating as these are on their own, but Vallely is careful to draw out his subject’s personal observations and feelings about every aspect covered along the way. This methodology is frequently counseled by folklorists, though seldom practiced.

As a musician John played with many differing ensembles, dance bands, marching bands, house ceilidhs, pub sessions. He could be playing at a fleadh cheoil one weekend and marching in an Orange parade on the following weekend. Such indifference to cultural barriers does not imply a lack of understanding or disregard for the merits of the cultures themselves. He is truly a magpie with a love of, and curiosity about, all of the cultural diversity in the music of his neighbours, no matter which foot they kick with. He is completely aware that, though the fife does not normally feature in recreational music, his ability to perform on that instrument and his expansive knowledge of it’s repertoire adds greatly to his interpretation of the more mainstream Irish traditional music. This is particularly true in the case of his prolific output as a composer.

About 65 of tunes written by John make up the centerpiece of this book. Even though he states that he did not make tunes himself until he retired in 1993 they must have been bubbling away in him and ready to erupt. They are lucidly written here and presented in large bold staff legible enough to even this short-sighted reader. Kennedy’s individuality is everywhere evident in the refreshing musicality of so much of this (mainly dance) music, Paradoxically, most of them could be absorbed directly into the tradition. The majority of them could be awarded the highest accolade a traditional musician can pay to a newly-composed tune: “You wouldn’t know that it was written!”

Future musical historians will be forever grateful to Vallely for his astuteness in eliciting from Kennedy the explanation for every tune title and the occasion which inspired the composition. These range, from the mundane, like the jig, ‘The Dog’s Hair’ made after listening to his wife Moyra, complaining about the hirsute deposits left around the house by their dog, Freeway. There is the sociologically interesting, like ‘The Rub Boards’ another jig inspired by the rhythm of a huge mechanized washboard in a linen mill. Geographical references abound, as in the reels ‘Craig’s Crossroads’ and ‘Boals Hill’. And it might be best to draw a discreet veil across for the origin of the jigs ‘Honeyballs’ and ‘Just Call Me Honey’.

Songs are also important in the musical life of John Kennedy. Unsurprisingly, the first song he learned from his mother was ‘Barbara Allen’. He is not a songwriter himself although he admits to altering or adding the odd verse where he deems it necessary. Four songs from local poets are presented in the book to which John has put airs. For some unexplained reason these are the only tunes not transcribed although they all may be heard on the CD. Another minor quibble I have is that a little more attention could have been paid to the textual transcription of these songs, as either inaccuracies have crept in or they were transcribed from recordings other than those reproduced on the CD. Eight other songs are reproduced in the book which are not to be found on this CD but can be heard on the Vetran CD ‘John Kennedy: The girls along the road’ (VT 137CD) published in 1999. His singing may be an acquired taste to many, as the quaver which is in his normal speaking voice comes across as vibrato when he sings. This is not a criticism, merely a statement of fact directed at those who do not know him. Those that do know that it is impossible not to respond positively to this hugely gregarious man when he performs.

The CD accompanying book is devoted completely to John’s musical compositions including the airs to the aforementioned four songs. The recording quality is excellent.

Only one instrumental piece ‘Snow in April/Craig’s Crossroads’, is unaccompanied. However, the accompaniment is tasteful and restrained on most tracks. Only on Tracks 6 (Farewell to Brandy etc.) and 12 (The Ring of Gullion etc.) does the guitar become obtrusive and on Tack 17 (Caitlin’s Song etc.) one wishes the microphone was placed at a greater distance from the bodhrán. All of the accompanists are friends and/or students of John’s and their enthusiasm for him and his music are evident on this enjoyable recording.

Last year I had the honour of unveiling a plaque in the comminty hall in Roadford, County Clare to the memory of the great storyteller Stiofán Ó hEalaoire (d.1944). The reason why the memorial was erected in the hall, rather than in the nearby graveyard where he is buried, was because the resting place of Stiofán can no longer be found. The grave of greatest documented Clare storyteller had been lost to posterity. This is an appalling reminder of how quickly the memory of individuals who have contributed enormously to the cultural fabric of our nation can disappear. To the Loughshore Traditions Group and Fintan Vallely we owe a dept for memorializing John Kennedy, for doing it while his is still alive and can be made aware of how highly he is thought of, and for doing it so well in this splendid production.